Doing What I Know Best

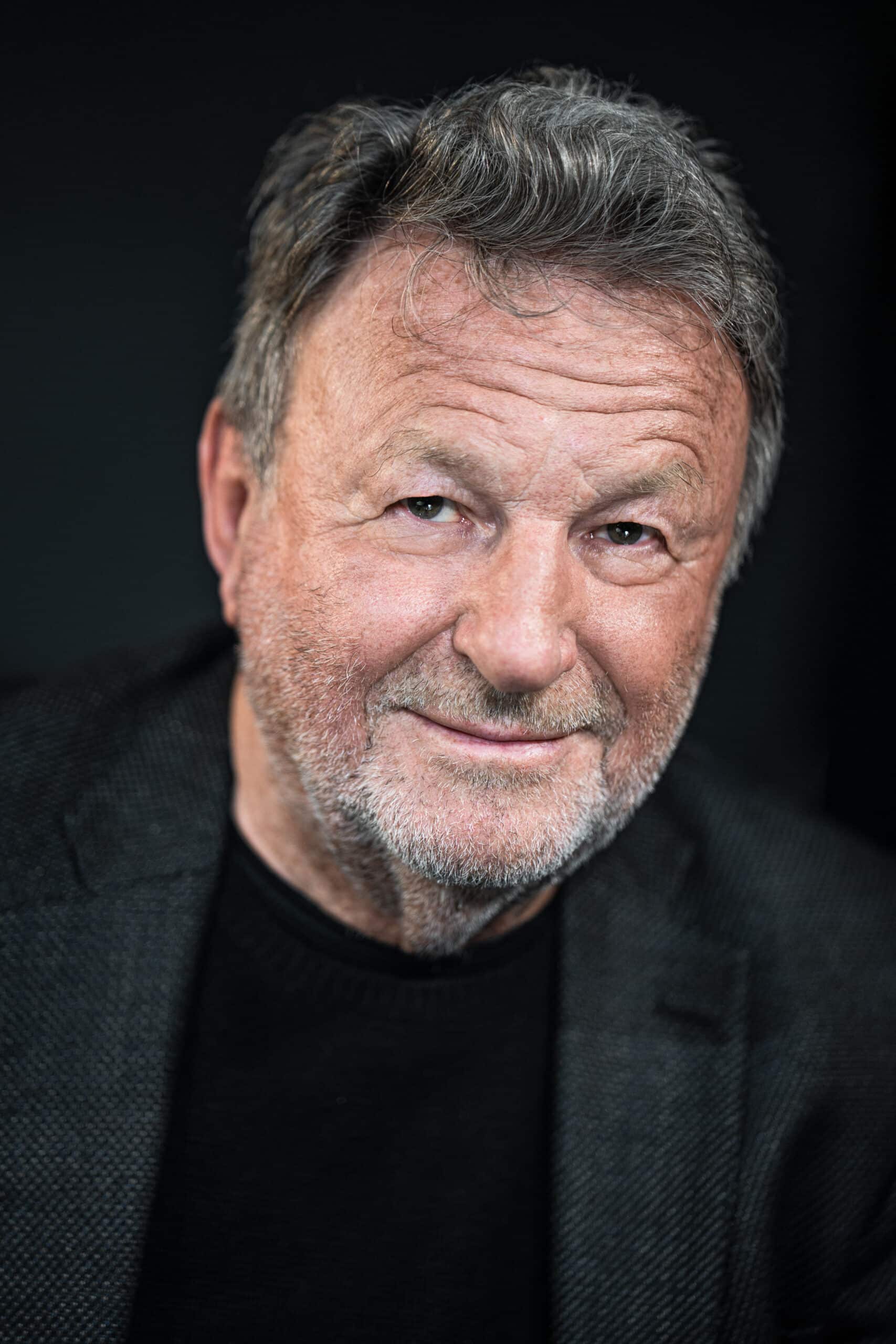

Józef Wojciechowski, the developer and founder

of JW Construction—a company that has built over 40,000 apartments in Poland—discusses the biggest challenges facing the Polish development industry with editor Kazimierz Krupa.

You’ve been building apartments and homes for over 30 years. How do you feel about the atmosphere surrounding you and your colleagues in the development industry? You’re often portrayed as the embodiment of the “bad guy.”

It’s hard to accept, but you have to face it. When something is lacking, someone has to be blamed. And since there aren’t enough affordable homes for people, developers are the ones blamed. There’s no other reason to stigmatize a group that is essential to providing the four walls and roof over people’s heads, as we’ve seen in recent years.

Do you think the debate about whether housing is a commodity or a right for every citizen contributes to this? It seems to mix two different value systems. Of course, housing is a commodity, but the right to housing is something that should be addressed by the state.

If the government didn’t interfere, we’d already be seeing some success. The reason housing is so expensive today, and inaccessible to young people, is largely due to the actions of those in power over the past years. They worked very hard to make it this way. For instance, the recent increase in land prices was artificially induced, primarily as an electoral tactic. President Kaczyński, for example, reduced interest rates for everyone, regardless of whether people were buying apartments for rent, investment, or as their first home. All developer resources were quickly sold because loans were cheap. That led to the movement to replenish land banks, and within a few months, land prices rose fourfold compared to three or four years ago. The price of land is the first factor that affects the final cost of a project that the customer has to bear. Another factor created by the previous government was the rapid rise in the minimum wage, which automatically increased the production costs of building materials and salaries for workers. The third factor is the wait time for permits. The procedures are so nightmarish that I can’t recall anything this bad in my 32 years in the industry. We’re talking about waiting a year or more for approvals for things like access to developments or utilities. The final customer has to pay for all of this.

Developers will operate under the conditions imposed on them since it’s a business. But what needs to happen for this madness to stop?

I’ve discussed this with many politicians. Solutions to simplify the system need to come “from above.”

I think putting the housing market back on track will be very challenging today. I’m not particularly optimistic. Why? I’ll give you an example of some friends who bought a piece of land for 20 million zlotys. A developer even offered to buy it for 40 million. But the talks started, and the situation became complicated, and eventually, the developer stopped picking up the phone. I told my friend, “Lower the price a little; you don’t need to make that much profit.” He said, “No, I’ll get what I want eventually. I’m not in a hurry.” This story shows that lowering land prices will be very difficult, if not impossible. Prices have been artificially inflated not just in large cities like Warsaw, Kraków, Poznań, and Wrocław. I get many offers, but the prices everywhere are much higher than they were three or four years ago.

What should the government do to improve the situation?

There are a few areas where changes should be made. First, there’s the issue of land for construction. What I’m about to say is controversial, and politicians are afraid of it, but there should be

a property tax. Initially, this should apply to commercial real estate in cities. Cities are not meant for industry; it should be moved to cheaper areas, and the land currently occupied by industry should be reclaimed for housing and people. The government can do this.

Second, the State Treasury owns land. Releasing that land could significantly impact the factors that affect the final price of housing.

It’s also important to ensure that we don’t wait for permits for longer than, say, six months. This can be done. If an incentive system were introduced for issuing these permits on time, municipalities would start working more efficiently.

Finally, one of the most important issues is the financial cost, which is currently astronomical. Even if the government doesn’t support first-time homebuyers with any programs, it should at least offer them some form of financing. The idea is for commercial banks not to charge these people interest rates of 8%, 9%, or 10%. One solution could be creating a special housing fund.

I think Prime Minister Tusk should consider this. Such funds exist worldwide.

How does it work?

It works like this: a commercial bank accepts an application, processes the entire loan, disburses the money, and then sends the paperwork to a special government unit, which issues bonds on the domestic and possibly international markets. These are some of the best bonds because they’re backed by real estate. This type of financing should cost 2-3%, plus a margin for the bank managing it. The total should be around 5%.

Do you see any opportunity in programs like PPP (public-private partnerships), either with the state or local governments?

First of all, I don’t see any activity in this direction. I remember the declarations, of course. The previous government promised

3 million apartments, then 1 million, 100,000, and a few thousand were actually built.

You observe the market in Poland, but also trends in the European and global markets. Where does Poland stand on the world map? Is it a green island, a red island, or a stormy sea around us?

I don’t want to be a pessimist because bureaucracy is not just

a Polish problem. Europe is riddled with bureaucracy. The Americans also claim they’re plagued by bureaucracy. There’s a general tendency to overregulate industries. It’s becoming a cancer that is starting to become dangerous. I think 30 years ago in Poland, it was easier than it is today, especially in my industry. I wouldn’t want to comment on industries I’m not involved in, because I follow the American principle that you should focus on what you know.