EUROPEAN DEFENSE UNION

We are living in a time of uncertainty. What we once considered

the stable and comfortable foundation of our security is crumbling

by the day.

The United States, which for decades guaranteed peace in Europe and provided military and political protection to its European allies, has now declared it can no longer do so to the same extent. In fact, the U.S. has stated that Europeans will soon have to ensure their own security and take responsibility for solving their own problems. While the U.S. is not planning to withdraw from NATO, it does intend to pull most of its troops out of Europe, leaving European nations to fill the gap.

The imbalance in defense spending within NATO has been a festering issue for years, and it was President Trump who ultimately forced the matter to a head. The underlying reasons are internal to the United States—stemming from a deepening domestic crisis, systemic inefficiencies, and the weakening of America’s global position in the face of China’s rise. This process of decline has taken years, and restoring the U.S. to its former standing will also take decades. It requires time—and money.

In line with Trump’s demands, Europe has started increasing its defense spending. Even the European Union has stepped into the defense space, marking a clear departure from its traditionally pacifist stance. However, it will take Europe many years to reach even 50 percent of NATO’s overall defense capabilities. The costs of replicating the American contributions to logistics, intelligence, satellite reconnaissance, strategic aviation, and naval power are immense and would need to be spread out over several decades.

These costs would be far lower, and the results much faster, if European countries weren’t so politically, economically, and militarily fragmented on defense matters. Everyone recognizes this weakness, but so far, there is no clear solution. Despite joint NATO and, more recently, EU defense programs—and despite a few multinational arms companies like Airbus, MBDA, or Eurocopter—many countries remain reluctant to give up their national symbols of power and pride. Companies like THALES or Leonardo, even though they have branches across Europe, are still owned by individual nations.

There are even issues with standardization, as demonstrated by the war in Ukraine. The famous NATO-standard 155mm shells can actually vary depending on the factory and intended use (e.g., long-range or precision), and in extreme cases, they can damage or destroy howitzer chambers. The same applies to tank ammunition and other systems.

The new American vision for NATO assumes that European countries will need to ensure the security of the U.S. from the other side of the Atlantic—essentially on their own—should the U.S. need to concentrate its military efforts, forces, and resources in the Far East. Moreover, in the event of difficulties on the front, Europe should be capable of providing military support to the U.S.

Things could become especially challenging if a formal military alliance between China and Russia were to emerge. Such a scenario could pose an existential threat to the entire West. As of now, there are no serious signs of this development, although close cooperation between the two nations is already a global political reality. In organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (a regional security alliance) and BRICS (a global anti-Western economic bloc), China and Russia are aligned. Of course, China’s potential is ten times greater than Russia’s. China is steadily pushing to turn Russia into a vassal state, while Russia—at least rhetorically—tries to maintain a semblance of equality and sovereignty.

A potential reset in U.S.-Russia relations would strengthen Russia’s position relative to China and help prevent further subjugation. But a full break between Russia and China is no longer realistic. The ties run too deep. Moreover, Russia’s openness to economic cooperation with China—particularly in raw materials—is seen as a guarantee (perhaps a false one, as seen in U.S. demands toward Canada and Greenland) that China won’t attempt to reclaim Siberia, which was illegally seized by Russia from China in the 19th century.

U.S.-Russia Reset and Poland’s Nuclear Dilemma

From the perspective of European defense, the most critical element—beyond the military might the U.S. brings to NATO—is the American nuclear umbrella. This was the primary factor that persuaded Sweden and Finland to join the Alliance. So far, there are no signs that this umbrella will be withdrawn, as NATO membership remains in the vital interest of the United States. In fact, the U.S. recently modernized its nuclear arsenal stationed in Europe, which is accessible to countries participating in the NATO Nuclear Sharing program (notably, the B61-12 tactical nuclear bombs with scalable yields).

However, military analysts have concluded that the U.S. nuclear umbrella alone may not be sufficient. One must consider Russia’s nuclear doctrine, which includes the concept of “escalate to de-escalate”—the idea of using nuclear strikes to halt enemy advances or resistance on the battlefield. Such use could be relatively “safe” for Russia if the opposing side has no nuclear weapons of its own and its nuclear-armed ally is unwilling to respond in kind, avoiding escalation to global war.

That’s why countries involved in the NATO Nuclear Sharing program—Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Turkey—have insisted on gaining operational authority over U.S. nuclear weapons in the event of war. They even threatened to withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and develop their own nuclear capabilities, as France once did. Collectively, they possess about 100 U.S. nuclear warheads delivered via specially modified aircraft. The UK has a similar status, having produced its nuclear arsenal essentially under an American license, with the U.S. retaining influence over its use.

Today, doubts surrounding the reliability of the U.S. nuclear umbrella have become a growing concern—not only for Poland but for all European countries not included in the Nuclear Sharing program. Even if Poland were to build a powerful conventional army capable of defeating a Russian aggressor in battle, a limited nuclear strike—say, on Olsztyn, Białystok, or Warsaw—could quickly force Poland into surrender and back under Russian control. In fact, Russia has already simulated such scenarios in its “Zapad” military exercises.

When Russia faced setbacks on the Ukrainian front, it reportedly prepared for tactical nuclear strikes. It was only restrained by its ally China. Meanwhile, the American response showed uncertainty—they threatened conventional intervention but seemed unsure of their course of action. The U.S. is entangled in great power politics, where national interests often take precedence over those of allies, all while trying to avoid a global nuclear conflict. Past examples include the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act and current negotiations over ending the war in Ukraine. The strategic interests of the U.S. do not always align with those of its allies.

This very concern led France in the 1960s to develop its own nuclear deterrent (the force de frappe), largely due to skepticism over the U.S. willingness to risk a nuclear war in defense of Europe. France refused to join NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group and chose strategic independence.

In today’s world, national nuclear weapons capabilities have once again become a critical matter.

Poland has been lobbying for years to join the NATO Nuclear Sharing program—without success. The U.S. consistently refuses, citing restrictions from the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, which prohibits the deployment of nuclear weapons or permanent stationing of significant NATO forces in countries that joined the Alliance after the Cold War (hence, U.S. troops in Poland are stationed only on a rotational basis). Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Poland and other newer NATO members have been demanding that this agreement be declared void due to Russia’s violations. So far, these efforts have failed, with the U.S. insisting the agreement remains valid—using it as leverage in broader geopolitical negotiations among great powers.

This issue is of fundamental importance to Poland’s security. Regardless of who occupies the White House, the U.S. position remains firm. After Poland’s most recent appeal regarding Nuclear Sharing, U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance reiterated the rejection on March 13 of this year. Only a complete breakdown in U.S.-Russia relations—such as a collapse of Ukraine peace talks—might prompt Washington to reconsider.

Poland has also proposed that nuclear weapons be stationed in its territory on a rotational basis. That too has been denied. Still, Russia is visibly alarmed. In December 2021, it issued an ultimatum demanding two treaties—one with the U.S., the other with NATO—containing terms far more aggressive than the NATO-Russia Founding Act. On December 17, 2021, the Russian Foreign Ministry publicly disclosed the humiliating draft texts of those treaties, which demanded sweeping concessions from NATO while imposing no obligations on Russia.

Russia believed its military strength and NATO’s weaknesses—perceived as relying solely on U.S. power—would allow it to dictate terms. The U.S. and NATO firmly rejected the ultimatum. Two months later, Russia invaded Ukraine. In light of that ultimatum, Russia sees its war in Ukraine as a conflict against NATO itself.

The proposed agreement with NATO includes a clause allowing Russia to withdraw from the deal at any time under any pretext. It is drafted in the form of a non-negotiable ultimatum aimed at a side that has “lost.”

Current U.S.-Russia negotiations have already led to some convergence of positions. From what is already known, Ukraine will not be joining NATO, and the stationing of NATO troops in Ukraine—even as a ceasefire monitoring force—has been ruled out. Russia, for its part, has proposed that troops from China or India could be deployed instead. Meanwhile, the U.S. has firmly rejected the idea of placing nuclear weapons in Poland.

Below is the content of the Russian ultimatum, which is currently part of U.S.-Russia negotiations over the terms of a potential reset in relations. It’s important to understand what Russia is demanding. The proposed agreements include:

- A commitment by the U.S. and other NATO member states to a policy of non-aggression and to refrain from actions that Russia considers harmful to its security;

- A halt to NATO expansion, especially eastward—particularly into post-Soviet territories;

3, A ban on the establishment of military bases and military activity on the territory of Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries that are not NATO members (such as Georgia and Moldova); - A prohibition on the deployment of intermediate- and medium-range missiles outside NATO territories and in regions from which they could strike Russian territory (such as Poland, which borders the Kaliningrad Oblast);

- A prohibition on deploying nuclear weapons outside the territories of the states that already possess them, and the dismantling of infrastructure that would enable such deployments (such as airbases for nuclear-capable aircraft);

- A ban on stationing troops and conducting military operations in Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries (including the Baltic states);

- The withdrawal of allied forces stationed in NATO member states that joined the Alliance after May 1997 (the date of the NATO-Russia Founding Act);

- The establishment of a buffer zone around the borders of Russia and its allies in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (such as Belarus), within which military exercises or other military activities involving brigade-level forces or larger would be prohibited (effectively limiting the sovereignty of countries like Poland within their own territory);

- A ban on flights by heavy bombers and movements of warships in areas from which they could strike targets on Russian territory (especially in the Baltic and Black Seas);

- A requirement for NATO combat aircraft and warships to maintain a specific distance from their Russian counterparts during encounters.

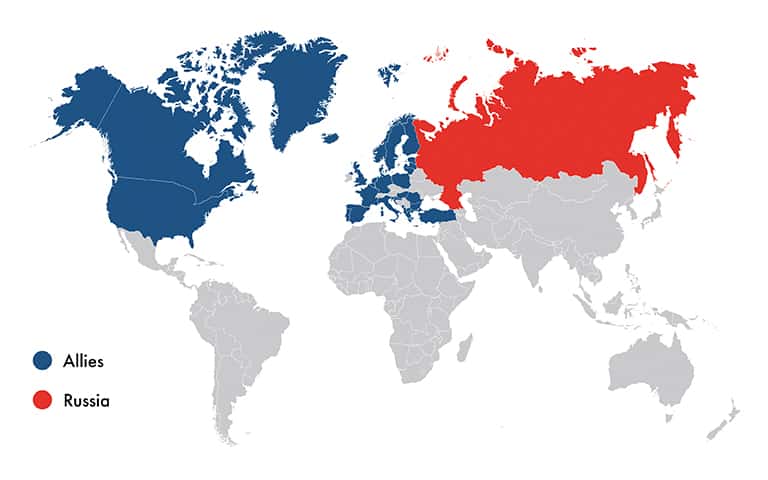

World map with NATO member states and allies including Sweden and Finland

Searching for Alternatives

For Europe to take responsibility for its own security and future within NATO, it will require both time and financial investment. The United States has demanded that defense spending rise to 5% of GDP, a reflection of the pace at which it may potentially withdraw from Europe. However, this target is currently unattainable for most NATO countries—especially considering that, nearly 20 years after agreeing to the 2% goal, eight NATO members still haven’t reached it. Politicians fear losing public support if social programs are cut or if defense budgets cause widespread economic strain.

Moreover, countries further removed from Russia don’t perceive an immediate threat—or any threat at all. Southern European countries, with the exception of Greece (due to its tensions with Turkey), increasingly see it in their interest to distance themselves from defense obligations. The situation is very different along NATO’s eastern front, in countries like Poland and the Baltic States, where the public is alarmed by the reawakening of Russian imperial ambitions. Ukraine may only be the beginning—something no longer just echoed in Kremlin propaganda but supported by U.S. intelligence reports made public shortly after Russia’s invasion (as confirmed by the U.S. representative to the UN Security Council in February 2022). Unless these countries voluntarily submit to Russia’s demands, they may be next.

A new benchmark of at least 3% of GDP in defense spending is now being proposed. The European Union, once a staunchly pacifist organization (it even refused to participate in Poland’s costly border wall project with Russia and Belarus), is now preparing a major rearmament fund of around €800 billion.

This financial challenge, alongside the U.S.’s strategic pivot, exposes a deeper issue: NATO’s internal cohesion is weakening. This threatens the alliance’s ability to act in solidarity during a crisis. For example, it could take Spain or Portugal several months to transition to a wartime footing—and mobilizing troops doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll be able to provide effective support.

Poland’s situation is increasingly precarious. The Visegrád Group was supposed to be Poland’s closest bloc of allies. That concept is now in doubt. Slovakia and Hungary are openly distancing themselves from Poland’s policy stance and appear sympathetic to Russia’s position in the war. Upcoming elections in the Czech Republic are expected to bring back former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš’s ANO 2011 party, which has aligned itself with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The group itself was created in the 1990s because the U.S. needed a mechanism to avoid negotiating separately with each Central European country. But the bloc was never truly cohesive.

Ambitious Czechia, once among the world’s top ten most industrialized nations before World War II, still harbors a superiority complex—especially toward Poland and Slovakia. Hungary dreams of reversing the territorial losses of the Treaty of Trianon and often manipulates its ethnic minorities in Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Slovakia remains torn between pro-Western and pro-Russian leanings. Over the 25 years of the group’s existence, its members have failed to economically integrate or restore their former Warsaw Pact-era defense industry cooperation.

Further south, the situation is not much better. Although the pro-Russian candidate Călin Georgescu was disqualified and barred from running again in Romania, the fact remains that most Romanians reject anti-Russian views. In Austria, it’s a similar story. The openly pro-Russian Freedom Party is polling above 30%, and any weak coalition government formed after the 2024 elections will likely have to accommodate them.

One of the leading ideas for strengthening Europe’s security is France’s proposal to complement the U.S. nuclear deterrent with its own nuclear umbrella. France developed its nuclear weapons independently and does not need approval from anyone to use them. It also has its own delivery systems. For decades, France’s force de frappe (nuclear strike force) has served only French interests. Once deemed sufficient, it was not further expanded—and France even dismantled its land-based missile silos in the central plateau.

France currently holds 290 nuclear warheads (compared to the U.K.’s 225), which is enough for a retaliatory strike. Since Russia’s key political, military, and economic centers are mostly concentrated west of the Urals—especially south of St. Petersburg—destroying all of Russia wouldn’t be necessary to deal a fatal blow. Military analysts have proposed expanding the French deterrent to 460 warheads to enable a Nuclear Sharing framework. One challenge is the lack of tactical nuclear weapons, which makes it difficult to escalate responses gradually in the event of a nuclear strike.

Nonetheless, France’s offer is currently quite attractive. The challenge lies in the fine print—cost-sharing arrangements and the acceptance of France as Europe’s security leader. France would need to formally guarantee nuclear protection for its allies. To some extent, this is already starting to happen. France is not part of NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group and is therefore free to negotiate independently.

There is also the issue of the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, which still prohibits the deployment of nuclear weapons or large NATO forces in new member states. If Poland builds up its military to the point that it can defend itself long enough to await allied support, then the only missing piece would be a credible nuclear deterrent—backed by publicly known and ironclad rules for its automatic use.

Poland, Lithuania, and Denmark have already initiated talks with France about this nuclear umbrella. France has also launched an effort to build a European pillar within NATO capable of acting autonomously from the United States. It has invited other militarily capable countries—Germany (185,000 troops), the U.K. (195,000), Poland (210,000), Italy (175,000), and France itself (270,000)—to take part.

Experience shows that the U.S. is more responsive to its partners when there is viable competition. Such a European defense pillar is now taking shape—possibly even under the name European Defense Union.

It may also be time to revise the treaty-based principle of mutual defense found in Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. As it stands, it does not impose a binding obligation for member states to provide military assistance to an ally under attack. In the worst-case scenario, a NATO ally could respond with nothing more than a diplomatic note—and still be in compliance with the treaty. A principle of automatic military response once existed in the now-defunct Western European Union. Reviving that could go a long way toward replacing Europe’s reliance on U.S. or French nuclear sharing—especially since, for now, access to either remains out of reach.