JAN SZCZEPANIK – THE POLISH EDISON

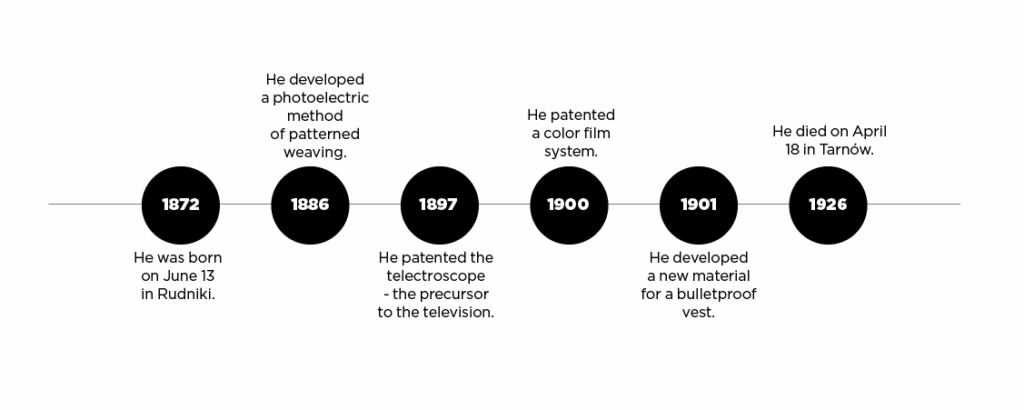

Jan Szczepanik was born on June 13, 1872, in Rudniki near Mościska.

This brilliant Polish inventor and innovator was dubbed the “Austrian Edison” by Mark Twain after they met in Vienna—a label the writer used only because Poland did not then exist on the map of Europe. Later, captivated by the Pole’s talent, Twain devoted two stories to him: “The Austrian Edison Keeping School Again” and “From the London Times of 1904.”

After his father’s death and an early separation from his mother, he grew up around Krosno, completing a teacher’s seminary. A teacher’s patience and a craftsman’s inquisitiveness stayed with him for life. Years later in Vienna, he combined Polish persistence with the imperial-and-royal hunger for innovations—and the mix proved explosive for the technology of the day. It was then that Mark Twain—fascinated by the young Pole—wrote his sparkling sketches about the “Austrian Edison,” spreading his fame in the English-speaking world.

He began as a teacher in village schools in what is now Subcarpathia and Lesser Poland. He later took a job at Ludwik Kleinberg’s photography shop in Kraków. There he learned camera construction, caught the creative bug, and began tinkering with inventions in photographic and film technology.

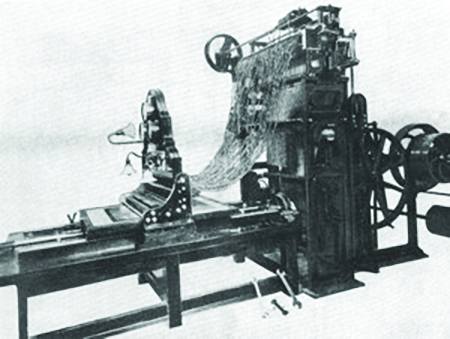

His first inventions, however, targeted the textile industry. Even while teaching, he visited local weaving workshops; moved by the hard labor of rural weavers, he pondered how

to improve fabric production. He was especially drawn to color weaving technology—highly complex at the time—performed with Jacquard machines invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard, operated manually using perforated cards (also called “pilots”). In 1896, Szczepanik developed a photoelectric method for patterned weaving that was cheaper than existing solutions and cut the production process almost tenfold, significantly lowering costs. He patented the method in Germany and later in Great Britain, Austria, and the United States.

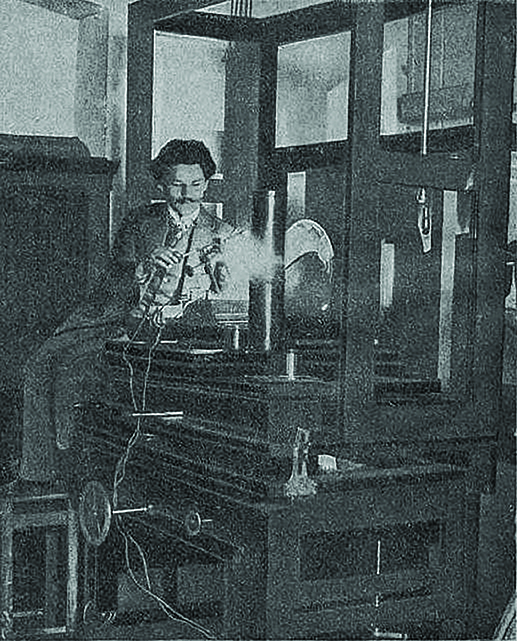

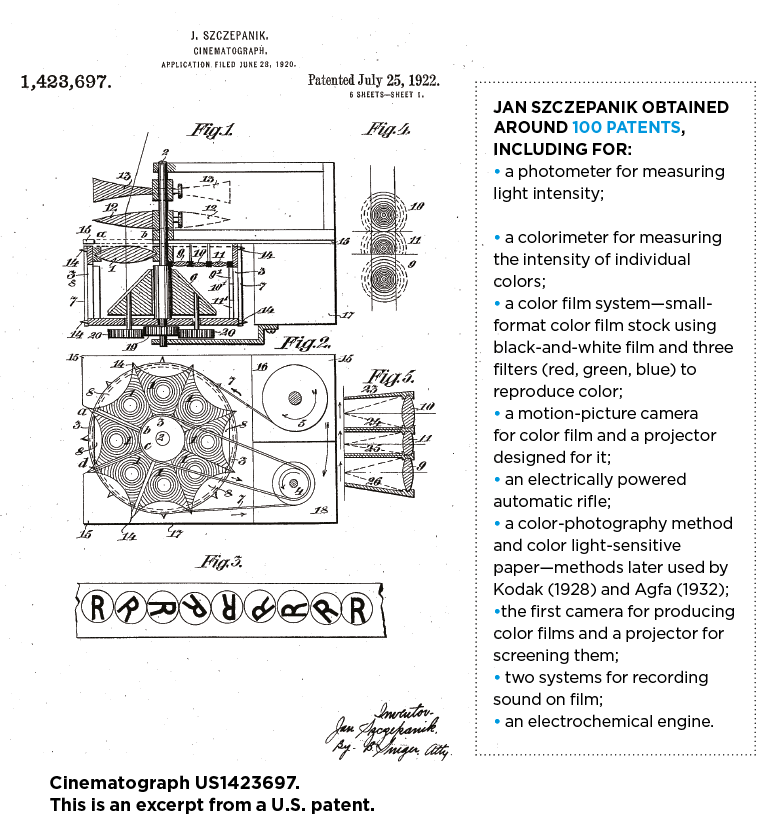

Color played a central role in Szczepanik’s workshop. He experimented with color 35mm film, tricolor filters, and screens (rasters) for faithful color reproduction. He also developed color-sensitive materials and color photography methods that, years later, entered the catalogs of major manufacturers (Kodak, Agfa). In addition, he designed and patented a camera and projector for color film and undertook the first experiments in synchronizing image and sound on film stock—laying the groundwork for later sound cinema.

in his Vienna studio.

The “television before television” thread in his biography is no myth. On April 3, 1898, the New York Times front page featured a drawing of the telectroscope, patented in London the previous year by Jan Szczepanik. The invention received British Patent No. 5031/1897 and was filed with the description: a telectroscope, i.e., a device for reproducing images at

a distance by means of electricity. The device could also transmit sound and was the germ of the television set. Though still at the conceptual stage, the very idea of segmenting an image into tiny elements and reconstructing it elsewhere—what we would now call pixelation and signal transmission—was well ahead of its time.

Telecommunications fascinated him too: from ideas akin to wireless telegraphy to sending simple images over a telephone line—early traces of dreams about remote seeing, i.e., video calls. His portfolio also included bold sketches of transport: a movable airplane wing, an early autogyro variant, an airship, and a submarine—evidence that he thought systemically and in multiple dimensions.

Szczepanik achieved worldwide fame with his invention of the bulletproof vest. In 1901 he devised a special material that combined silk with steel plates in a multilayer structure capable of fully absorbing a bullet’s energy and protecting the body beneath this protective garment. Such a vest saved Spain’s King Alfonso XIII from an assassination attempt; in gratitude, in 1902 the monarch awarded Szczepanik the Order of Isabella the Catholic. Long before the 20th century discovered Kevlar—created by chemist Stephanie Kwolek, of Polish descent—Szczepanik was testing multilayer fabrics that could stop handgun rounds. Well before the word “ballistics” rose to prominence, his solutions brought him international recognition and a royal decoration. In collective memory, this became the most cinematic legend of the “Polish Edison.”. What is extraordinary about Jan Szczepanik is not merely the technical art, but the chain of applications: from the weaver’s workshop to the movie theater, from the photographer’s lab to the telephone line. Today we speak of technology convergence; he practiced it a century ago. Thanks to that, Szczepanik’s biography is not a collection of dates but a map of connections—where an idea becomes an invention, and an invention becomes everyday life.