Ekonomics of Rational Behaviors

The world nudges us, fights for our attention, and in the middle of it we try to keep it together…

And so it happened: an important meeting, everything prepared, and I walk out of the room with that familiar thought: “This wasn’t how it was supposed to look.” Reality, like a river, likes to change its bed. Sometimes it flows according to plan; more often, it goes its own way. At this bend two sisters meet: behavioral economics and the economics of rational behaviors (ERZ). The first shows how the world nudges us to act— a road sign, the order of options in an online store, algorithmic prompts. The second looks inside. ERZ organizes it into four simple questions. First: my aspirations. What kind of person do I want to be at work and after work, meaning how to behave in concrete terms. Which rituals—learning a language, an hour of running, a conversation with my partner, a lesson with my child—build me for the long term, and which rather don’t?

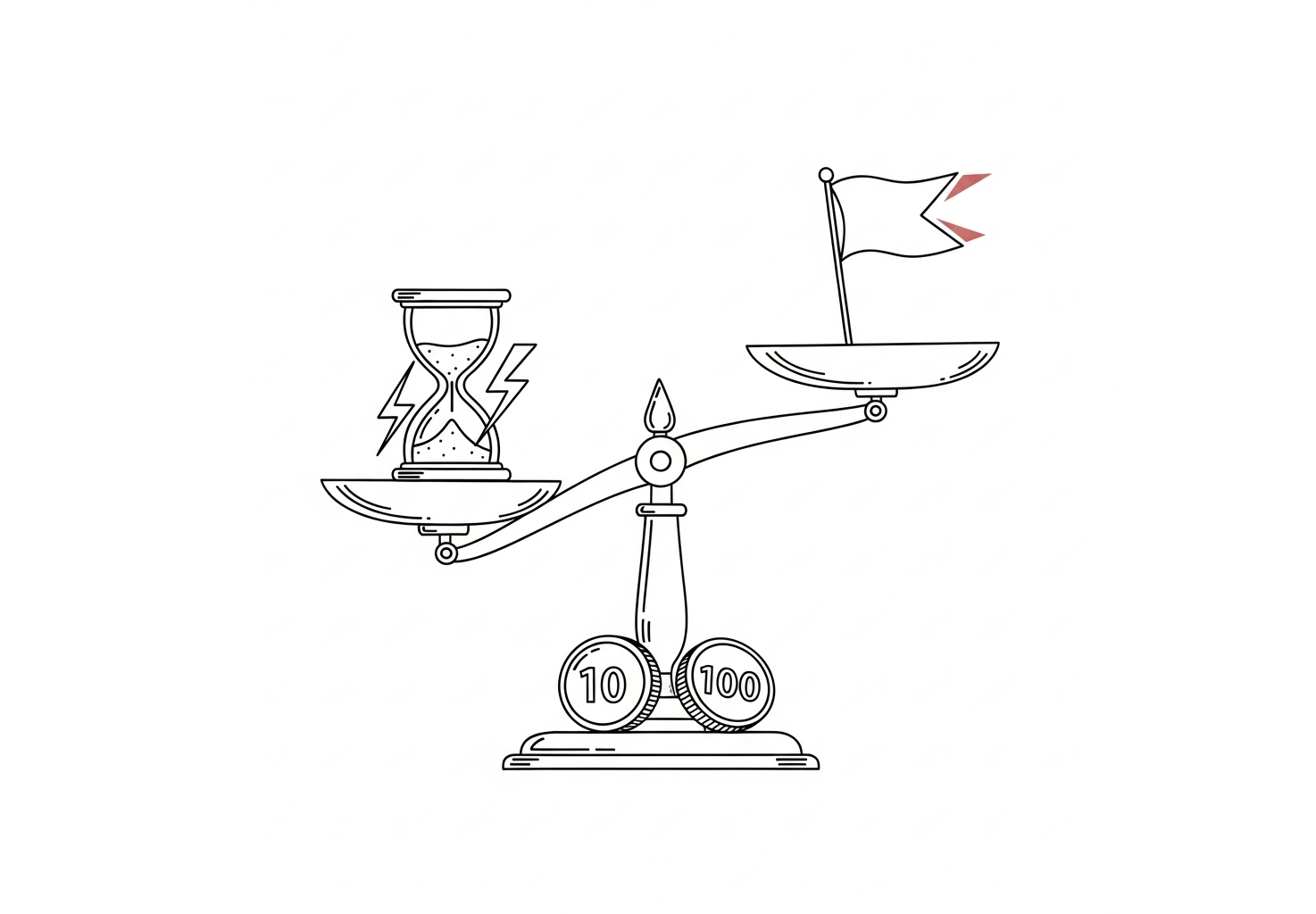

Second: the denominations of behaviors. How much do I really pay in time and energy for a specific gesture, behavior? Is a call to a difficult client worth a hundred for me, and coffee with a friend a ten?

Third: weighing. What brings me closer to the goal, and what only tires the muscles without moving forward?

Finally: attention—it isn’t inexhaustible, and on top of that it changes over the course of the day, especially as the CV gets longer…

Let’s take Staszek: at the office he pays in low denominations, because he invests in his grandfather’s workshop— in the smell of wood and the meaning of working with his hands. His value account grows after hours. Ludwik is the opposite: he lives on data, after work he feeds his curiosity with podcasts, and he weighs a conversation by the copier as an opportunity cost. Both are playing the same game, but on different boards. The costs and gains result rather from the fact that we rub our heads against reality where both the shape and our curiosity fit.

The world will push us, nudge us, irritate us positively and negatively— we will give these flicks meaning, but it matters that we do so. The world of homo sapiens, a species not so far in social behaviors from bonobo (pygmy apes), differs from them by only 1.3–1.8 percent in DNA structure—this world is simply like that.

Yet the profit-and-loss account is best done in one’s own wallet of behaviors. When we know our aspirations, can assign denominations, and weigh honestly, something like “jet fuel” is born:

a readiness to pay a high price for what is truly ours. Then even if the river changes its bed again, we still hold our course. Not perfectly, but consciously. This is the most sensible economics of everyday life. When I again walk out of the room with the thought: “this wasn’t how it was supposed to look,” I’ll smile to myself: it’s only a signal to adjust course, not a reason to capitulate. The direction remains. Forward, further. Now. Along the way we will also meet those who care that there be a log under our feet. That too is human behavior. What matters is to be on the path, because not everyone likes or prefers exactly the same thing as others, and that too can be irritating.