Catching Up to Japan

The phrase “catching up to Japan,” often celebrated in Polish media, is certainly music to the nation’s ears. However, it doesn’t hold up when measured against most key economic indicators.

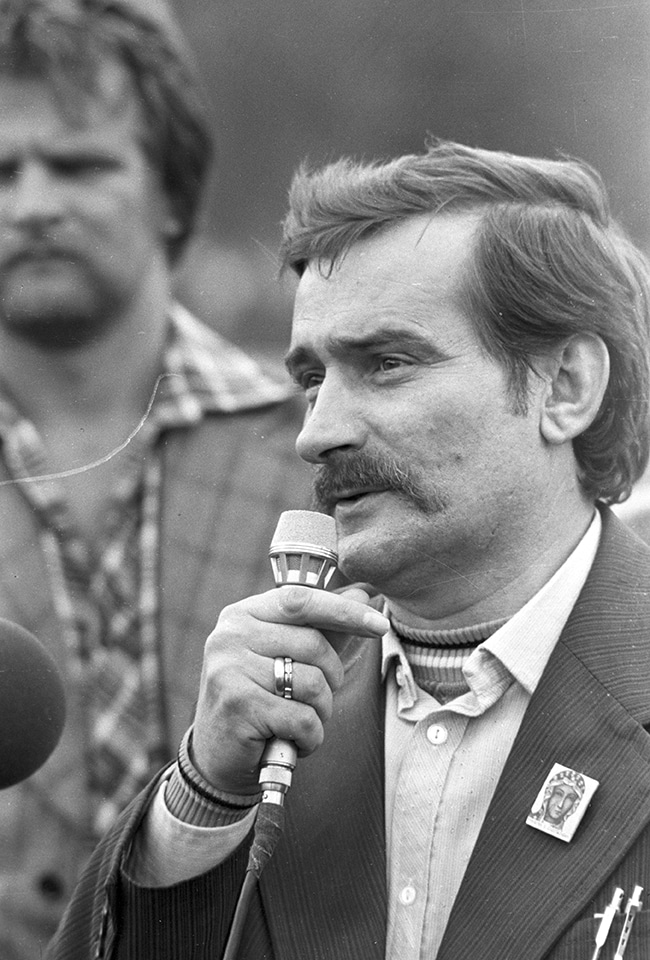

The concept of creating a “second Japan” was first voiced by Lech Wałęsa back in 1980. At the time, it sounded like a fantasy. Japan was in the midst of its economic golden age, and the world was speculating whether it might even surpass the United States in terms of wealth.

A Measure of Success?

era—and Poland has certainly experienced a rollercoaster ride during that time. The 1980s and early 1990s were marked by economic collapse and widespread impoverishment. But since then, Poland has transitioned into a period of dynamic growth—at least in terms of GDP. When Wałęsa made his famous remark, Poland’s GDP per capita, measured by purchasing power parity (PPP), was only about 35% of Japan’s. By last year, Poland had nearly closed the gap, and barring any major disruptions, it is on track to surpass Japan in this metric as early as next year.

For those who view post-1989 Poland as a story of uninterrupted success and unprecedented growth, this milestone is a source of great pride. It is often pointed out that Poland has already overtaken other European countries in GDP per capita (PPP), such as Portugal and Greece—nations that for years represented a much higher standard of living. Catching up to Japan, especially given Wałęsa’s historic quote, holds symbolic weight, illustrating how far Poland has come since the days of the Polish People’s Republic.

Still, GDP per capita (PPP) is not a perfect measure of national wealth. While it is useful, its limitations must be acknowledged. Russia, for example, also performs well in GDP statistics, despite the fact that its economy is heavily geared toward military production and its citizens experience a reduced standard of living. In some countries, high GDP per capita figures are driven by unsustainable levels of public spending.

A better indicator of actual wealth is income. And here, Poland has indeed made extraordinary strides over the past few decades. In the 1980s, Polish wages (adjusted to dollars) were just one-fourth of those in Japan. Today, they have essentially equalized with a nation once considered the global leader in high-tech innovation.

Chasing a Slowing Giant

Still, while celebrating Poland’s achievements, it’s important to recognize the challenges that put this “catching up” in a different light. First, one cannot ignore the fact that Japan has been in a prolonged economic slump since the 1990s. When Wałęsa made his “second Japan” comment, Japan was growing at an average of 4–5% annually, and its corporations were snapping up iconic American firms. After 1990, however, growth slowed to just over 1%.

Following the bursting of Japan’s asset bubble, the country entered a period of economic stagnation. This was later compounded by a demographic crisis that now looms large. Japan’s public debt has soared to an astronomical 250% of GDP, severely limiting its capacity for renewed growth.

In this light, Poland’s catch-up story resembles more the overtaking of a sluggish, aging billionaire than a sprint to match a vibrant and dynamic competitor. Japan faces serious population decline, which it is only now beginning to counter with increased labor immigration. But fundamentally, it remains the first nation in the world to confront the painful realities of a shrinking workforce.

Still, Japan possesses something Poland has not only failed to develop over the past 45 years but also lacks the infrastructure to pursue: globally recognized brands. Japan is home to dozens of world-class corporations—automotive, electronics, chemical, pharmaceutical, banking, and finance—that are industry leaders on a global scale. These grew out of the old zaibatsu model and continue to drive Japan’s international standing. If Poland had even a single homegrown company on the scale of Toyota, Sony, or Nintendo, it would be hailed as a national treasure. Instead, Poland’s market is dominated by foreign multinationals and state-owned enterprises—often weighed down by political appointments and stuck in mediocrity.

The Middle-Income Trap

Unfortunately, the chances of Poland producing its own global business leaders remain slim. The country’s economic and political system has long favored foreign investment over the development of domestic capital. Even more concerning is the falling rate of domestic investment. While Japan has consistently devoted around 25% of its GDP to investment, Poland’s investment level has recently dropped to as low as 18%.

Despite the rhetoric of success, Poland is likely to face serious challenges in maintaining its current growth trajectory. Demographically, the country has already begun to shrink—just like Japan. The recent wave of peaceful immigration has peaked, and future gains will be harder to achieve. Moreover, new EU climate policies are already leading to layoffs and bankruptcies, stifling industrial growth.

Perhaps most troubling is the risk of losing national sovereignty as the push for deeper EU integration accelerates. If Poland relinquishes the right to make independent economic decisions—a likely outcome of further federalization—it will lose the ability to develop and protect its own competitive advantages.

In reality, “catching up to Japan” looks more like a mirage than a milestone. Technologically, financially, and politically, Poland and Japan are still in entirely different leagues—and that is unlikely to change anytime soon. GDP per capita (PPP) may reflect dynamic trends, but it is a poor measure of real power or global influence. A far more worthwhile ambition would be for Poland to foster its own world-class industries capable of rivaling Japan’s. In that regard, little has changed since 1980.