Transforming the CEE Region into a logistics hub of the future

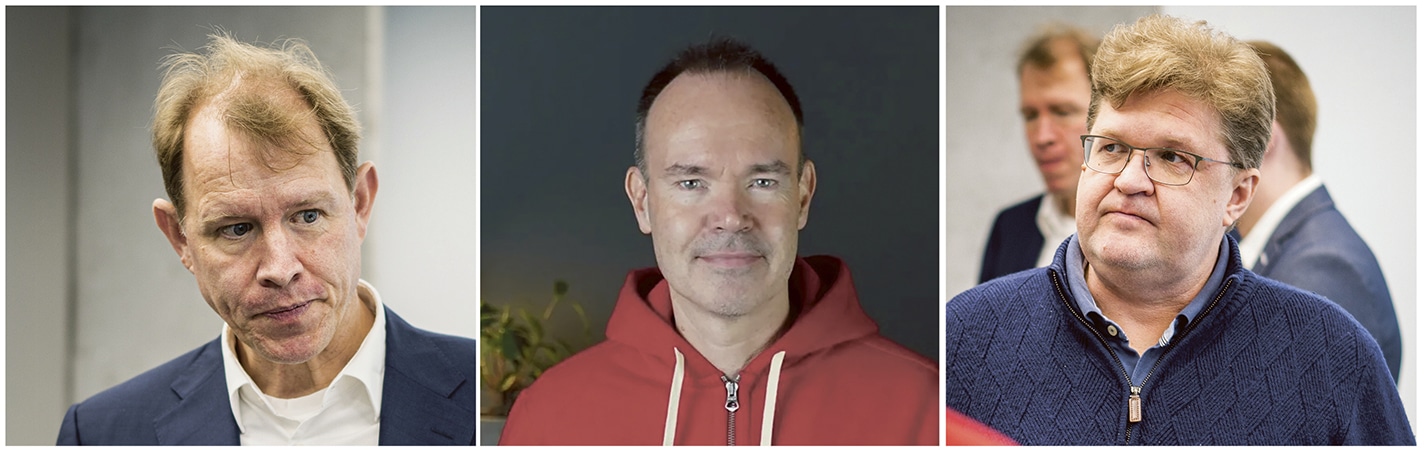

Sylwia Ziemacka talked to Kustaa Valtonen, an Entrepreneur and Angel Investor, Founding Partner at Finest Bay Area Development; Peter Vesterbacka, Founder of FinEst Bay Area and Slush, also known as the Mighty Eagle at Angry Birds, for many years taking that brand to unprecedented heights; and Frank Schuhholz, Founder at FMS Advisers, an expert in multimodal and intermodal-based supply chains across Europe.

The COVID-19 epidemic and the war in Ukraine have shown even more clearly how crucial the role of logistics infrastructure, including railways and seaports, is from both a civilian and military point of view. Also, the declaration of Finland’s accession to NATO has increased its importance as a partner country for Poland and the Baltic States.

How do you see the potential of Poland and CEE in terms of further development as a European logistics hub?

Frank: What we’re seeing already is that the center of gravity is definitely changing. Also the geopolitical situation is changing and we see the US, EU and China starting to move apart. This has resulted in more and more companies looking at their value chains and considering eventually having their production closer to their customers. Here we definitely see an emerging trend with business leaders in Europe starting to favor countries like Poland and the CEE region, establishing more resilient supply chains, as well as being closer to 480 million European consumers. This is one of the reasons why Poland should, in my view, lose its humbleness, raise its voice and say, we can do better, we can do more.

Peter: Of course, geography is what it is. Poland is really at the heart of Europe, the new Europe. Once we get the war in Ukraine finished, it will put Poland in an even more interesting position.

How do you define new Europe?

Peter: I mean, we have Ukraine on our side and Russia out of the way, so then things will get a lot more interesting and a lot better.

The Polish position in the logistics chains is crucial. From the Finnish or the Nordic perspective, we offer Arctic access for Central Europe. So it’s not only about how we access Central European markets, but also how Central Europe accesses the Nordic markets.

Would a tunnel between Helsinki and Tallinn facilitate that connection? Tell us a little bit more about the project. Your idea of creating a tunnel between Helsinki and Tallinn has gained new life due to the war in Ukraine and the expected Finnish accession to NATO. Where are you now with the project and how do you look at Poland and CEE in terms of the development of your project?

Kustaa: The project once completed will be the longest undersea railway tunnel in the world. It is being built by drilling, using tunnel boring machines and is entirely underground for the whole length of 103 km. There will be two tunnel pipes, one for freight traffic and the other for passenger traffic. It will connect two metropolitan areas into a single whole, reducing the current travel time from 2.5 hours to 20 minutes, making this intra-city rather than inter-city travel.

The gauge will be the euro gauge. So that’s good news for operators, able to access the Finnish markets more easily.

We are now working on designing and planning and running the environmental impact assessment. In Finland, we are pretty far along with the EIA. In Estonia, we are still waiting for things to happen.

When you introduced the idea of the tunnel a few years ago it was a purely private project. Has anything changed due to the current situation as the tunnel becomes the strategic infrastructure for Finland?

Peter: It is still a private project. I know that we are joining NATO, so it’s a NATO-compatible tunnel. So not only will we be able to move people and products through the tunnel, but it will also be important for military mobility. The war in Ukraine has shown us that it’s still important to have the capability to move a large amount of heavy equipment and people around fast.

Finland has a long border with Russia. With the tunnel we will get a better connection to Europe through the Baltic States and Poland. So I think that it is more important than ever.

We’re reducing travel time from Helsinki to Tallinn from 2 hours to 20 minutes. So it’s really like a metro connection, making Helsinki, with its 2 million people, a unified metropolitan area. it’s also becoming a major epicenter of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Is the Finnish government more engaged in your project?

Peter: Governments come and go. We have had three governments in Finland and three also on the Estonian side during the project so far. So again, I think that government engagement depends a little bit on who’s in power. We have elections coming up in April in Finland, so we will see how it goes.

But the political parties in Finland are very positive about the project. Finland needs a good connection with Europe so this infrastructure is super important. Now the only way to access Europe is by sea.

Also Estonia had elections recently and the winning parties are all very supportive of the tunnel project and the overall Finest Bay Area development. We have a shared vision of where our part of the world is going and needs to go.

Kusta: Maybe to add to that, yes, it’s a private project, but of course we do collaborate with the government. They set the laws and the regulations and we need to comply with them. So it’s quite clear that we follow what they say.

But in terms of the financials, is it purely private investment, as initially planned or does it now have governmental support?

Kustaa: It’s basically a completely private project. Because of that, we can move things faster. But as I said, we need close partnership, close collaboration not only with the Finnish, but also the Estonian government. And also it’s also connected to European infrastructure. So that is very important.

Europe wants to stay competitive in the global competition. Looking at China or Japan, they are building better and faster than we are, so how can we expect to be competitive? We need to make sure that national governments and the EU understand we need to be a bit more ambitious in general.

I think all of Europe is a bit too modest in our ambitions when it comes to connectivity, but maybe we’re also not really acting as a single unit.

Let’s talk for a moment about the Central Communication Port (CPK), the ambitious airport project in Poland. When looking at those two projects together – the tunnel and the CPK – what’s their potential to transform the region and connectivity between the North and South.

Frank: The CPK is an important project not only to enhance the capabilities of airfreight in Poland and the region, but to make it a multimodal logistics hub.

So it’s not only about the airport, but also the railway infrastructure investment closely connected to it. Potentially we’re talking about up to 1,600 kilometers of new railway lines that will be constructed, linking first into Rail Baltica, then leading into Finland via the tunnel to make it really a seamless means of transport. Right now it’s two hours of ferry passage for passengers and even eight to 12 hours for cargo because you have to shift from rail or road to a ferry when going to Finland. And then when you arrive in the other country you have to switch again. That makes cargo flows ineffective. And that is something which in the new world, in the new set up, I think is very important. We need to be attractive not only for producers, manufacturing companies, but also make it an attractive region to live in and also be present in the global market where regions start competing.

Let’s face it, we have 480 million people, 480 million consumers. And there is a lot to do to improve the situation from a supply chain perspective. We’re not only talking about additional railway lines, but also communication, IT, cybersecurity and critical infrastructure. All that we have right now is coming under the spotlight due to the war in Ukraine.

We see how important these projects are for the future. Also from a military perspective. The eastern border of Europe will be in the spotlight for the long term. That is for sure. And it’s not only about the military. Supply security from a Finnish perspective has always been crucial.

It’s also about making sure companies have enough different supplies in stock at any given moment. Supply chain resilience is a phrase that has moved into the standard vocabulary of decision makers. Let’s face it: having left Covid behind us and being witness to the ongoing war in Ukraine, we are becoming aware that we will be living in a multipolar world. Living in a post-Covid world, experiencing supply chain disruptions, with heightened geopolitical tensions and high inflation, we have to acknowledge that we are living in a poly-crisis world. Everything seems to be coming together right now and we have to manage that.

In this context, we have to see what we can do together for the CEE, Baltic and Nordic region and how to connect it with the rest of Europe. And how to undertake infrastructure projects in a much faster, much more ambitious way in order to be really on top of what the future will bring us.

Are there any benchmark projects in Europe or elsewhere around the world that show how quickly we can expect such projects to come to fruition?

Kustaa: One of the great examples was the Olympic line for the Winter Olympics in Beijing – the Beijing Zhangjiakou 174 kilometers of fully automated and fast rail.

Peter: Also, Tokyo upgraded the fast rail for the Tokyo Olympics. So I think both the Beijing and Tokyo Olympics were good triggers for China and Japan to speed up.

And I think that, again, we need to be faster at constructing infrastructure. Of course, we all understand that there are two different models. China is a different political system but we can’t always use that as an excuse. Political leaders in Europe say that in a democracy, nothing happens fast. But as citizens we need to demand more and not accept that.

Frank: To add to that is what we see in Poland. There’s a catch up effect here in terms of the logistics industry and for example the number of warehouses being constructed.

In Western European countries citizens have already developed the NIMBY phenomenon – Not In My BackYard … they simply don’t want these enormous buildings in their neighborhoods anymore as they impact the landscape but also the usage of local infrastructure by additional trucks moving in and out.

And when I drive through Poland, I’m always astonished that there are new warehouses popping up, 800 meters long, a hundred meters deep and 20 meters high being constructed. And you just ask yourself, how long will that go on without inhabitants eventually opposing such developments.

And that is the opportunity to think about this: what Poland should do for the next 20, 30 years. How to design logistic ecosystems in a much more sustainable way? As we all agree, we don’t want all this truck traffic, simply because it’s becoming a nuisance and it’s polluting, but we cannot do anything without moving some cargo. As infrastructure will eventually not grow as fast as now, and while still aiming at becoming a future production and logistics hub, we have to think about how to cope with these topics in a sustainable and resilient way. And I think this is one of the challenges where the region especially can learn much from others.

From Finland, from the Baltics into Poland and the CEE region – there is so much to anticipate for the next 20, 30 years, to make it a liveable country, not to plaster everything with warehouses. Poland hasn’t lost its attractiveness for logistics, because a lot of e-commerce activities are provided out of Poland into Western Europe. But that also needs to get acceptance from inhabitants, from the people living there, and making it a future proof, resilient concept.

Now everything is focused mainly on the western border. And there is still huge potential on the eastern border, right? We also have Via Carpathia, which I think really opens the potential of the east, especially its connection to Ukraine.

Frank: As you just mentioned, in Ukraine there is so much agricultural and other cargo now being diverted from the Black Sea ports, which are not as accessible as they were before.

A lot of cargo is now moving towards Poland, also Hungary and Romania. But the main share is going to Poland, so how to cope with it? You simply cannot do everything by truck. You have to use rail and connect it with the Polish ports. The point here is how to make this a future proof concept.

And there will be a lot of changes when it comes to cargo flows, because the war will be over at a certain point and then more cargo will also start to move in. If you do not have the logistics infrastructure for that, how are you going to handle it? Do you have the right railway lines? Do you have the right terminal infrastructure in the ports as well as in the hinterland alongside railway networks? All these kinds of things have to come into play.

Peter: This is something that we need to do in Europe, to make sure that from the EU level down we introduce competition at all levels, also on the operations side.

We need to get pan-European operators. That is something super important for the passenger side, but also for the logistic side that we open up and we need to make some really bold moves. We need to introduce more private players into this and ideally get rid of national monopolies. Europe is about freedom, movement of people and goods and free markets and entrepreneurship.

So it’s not only about the infrastructure, but also about transfer of technology, transfer of knowledge, transfer of innovations and European values, freedom, democracy and human rights.

Last question: looking at the current geopolitical situation in Europe but also the European position on the global map, are those projects that we have discussed also aligned with the global ambitions of Europe? Will they serve Europe as a whole or is it more about regional projects?

Kustaa: For us, the tunnel project is an innovation platform. It’s enabling a lot of things to happen, using this megaproject as a platform. One example is a Slovakian company that we have been working with on plasma drilling technology that helps us to do the boring of the tunnel much faster. This is a great example of how we can promote local European technologies and grow together.

Frank: Just a small example with regard to connecting European regions. Recently, two renowned companies from Poland and Spain started cooperating on an intermodal connection. A producer of furniture has decided to use an intermodal rail connection from Poland to Spain whilst a producer of fashion is filling the train back to Poland. They promote it as the longest intermodal connection in Europe, 2,000 kilometers. Let’s add another 1,500 kilometers to Finland. Imagine that you can do 3,500 kilometers in one go! That is something which eventually should be taken as an example of how Europe can develop and should develop in order to ensure that the regions are interconnected and that this is a unified Europe.

And let me also hint at the logistics conference ‘Connecting CEE – Transforming the region into a logistic hub of the future’ taking place in Warsaw on the 9th and 10th of November 2023, which will be organized by CEE Connectivity and will be dealing with exactly the topics we have discussed here.

We can definitely say that infrastructure is like the blood circulation system. So if we want to treat Europe as a whole, we need to have a system that can transfer nutrients all over and not just to some parts.